Towers of Bologna

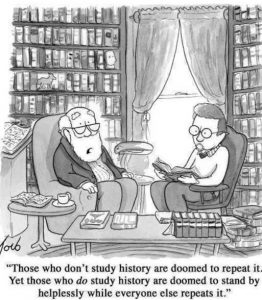

Over the years I’ve developed a love-hate relationship with theory.

Love:

- theory is powerful, for explanation and prediction and actually doing stuff

- theory is distancing, both requiring and allowing you to set your emotions aside for a while

- theory puts things in perspective, demanding that you look at more than your own individual feelings or experiences

- theory is rigorous, highlighting inconsistencies

Hate:

- theory is inadequate, never catching all the details

- theory is manipulable; there are enough data out there for anybody to build a theory supporting any conclusion

- theory is rigid, not welcoming alternative explanations

- theory is reductive, ignoring individuals in favor of categories

- theory usually leads to nonsense, if carried far enough

- theory is often a substitute for original thought

I guess the best simile I know for theory is the tower. One builds up and up and gets a wider view, but what will one do with that view? Paint landscapes, see people in need and go down to help them, or plan conquests? Will one live up in the tower, happily removed from the mess below? Will one get the god’s eye view so horrifically described in my least favorite pop song: From a distance, we all look like friends? Or will one identify a landscape full of deplorables?

Or, as time goes on, will one be more and more busy defending that tower, both against outsiders who want to get in and against folks who want to take its bricks and build something of their own with it? I hang out in a conservative christian space online, and get to see people hunkered over their one or two remaining bricks, snarling at the world.

What really has me thinking about theory is that our school has become a Hispanic-Serving Institution, so we start the year with discussions of what demographic categories our students fall into. But for me, one advantage of being an HSI is that we have enough latina students that they display variety and I can get beyond viewing them as examples of a category. Theory demands that its authors have categories and generalizations, but my job is to get past those and meet my students as individuals. Isn’t that the goal for almost all of us?

I was raised to think that categorizing people by race or ethnicity was wrong. I have the same reaction to it that some people have to discussions of humans as animals, probably for many of the same reasons. But just as physiologists must view humans as animals to construct our theories, social scientists probably must categorize them by race and ethnicity to build theirs. A lot of the world’s work must be done up in those towers.

Thing is, is that work fit for public consumption? Or are we folks up in the towers corroding ourselves with concepts and actions and theories that should not be inflicted on the body politic? Scientists have always done things you shouldn’t try at home, and often enough they have been poisoned by those activities – poisoned physically or morally. Someone who has spilled sulfuric acid on themselves or performed a vivisection has been changed in ways we don’t want the general populace to be changed.

Does this apply to social science theorizing, as well? Is thinking about people as categories necessary but corrosive?

Dissection table, University of Bologna

When I was in Italy, I spent a day in Bologna visiting their old dissection room, where the public might be invited to watch disassembly of cadavers. We no longer see that as good clean fun. One day, we may feel the same about 90% of the current theoretical dissection of humanity.

Bologna also contains a bunch of tall, tall towers, built by individual families for nobody knows what. There used to be more; they were built during a time of war, and most have been torn down and abandoned. We can only hope.