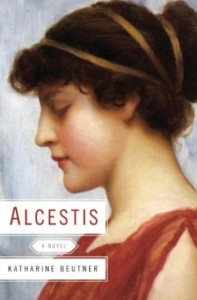

The #feministSF twitter chat week before last took up Alcestis, by Katharine Beutner. This is the first time I’ve only bought a book as an audiobook, without having a hard copy to check facts in, so if I have missed or misinterpreted details, please correct me!

The #feministSF twitter chat week before last took up Alcestis, by Katharine Beutner. This is the first time I’ve only bought a book as an audiobook, without having a hard copy to check facts in, so if I have missed or misinterpreted details, please correct me!

Greek myth. How many of us were introduced to it by parents who were unaccountably eager to give their innocent children a book that started with Kronos eating his own infants?

I liked my big illustrated book of Greek myths. The crowd of gods, nymphs, fauns, and hangers-on was like a treasure box. So I could sympathize completely when, in the twitter chat, Ms Beutner told us that it was Alcestis’ 3-day silence on returning from the dead that irritated her into retelling the story. What happened in the underworld, and why was Alcestis unable to talk about it on her return, as if her experiences with the gods and their realm were unimportant?

This novel captures the excitement of myth. The gods in Alcestis are real, inhuman, and mysterious. The otherworldly setting in Hades fascinated me, and had me stopping the audiobook to look things up (asphodel, adamantine). Hades himself was intriguing, and Persephone sinister. They were so different from the pictures of them I’d gleaned from my long-ago childrens’ books that even though the differences were not comforting at all, I was hooked. I wanted to know more about them.

The book is really about Alcestis, though, and this part of it I found less satisfying. The book brings us inside Alcestis’ head with no compromises or sops to the modern reader. This Alcestis is not a liberated 20th century girl in Greek clothing. She not only doesn’t control her own fate, she doesn’t think about the possibility. Even when she decides to die in her husband’s place, it’s because she foresees herself starving as the coward’s widow. Why? What makes her so accepting of her helplessness?

At first I thought the original myth of Alcestis must have been so embedded in both an oppressive human culture and a mythos of thoughtless, exploitative gods that it would be hard for any retelling of it to give the heroine real agency. But then I read Euripides’ play and found a far feistier Alcestis, giving her husband a good talking-to in the days between her sacrifice and actual death – days which the heroine of Beutners Alcestis does not have, as she is immediately taken away by Hermes. Euripides’ Alcestis points out that she could have just let her husband die and then married somebody else, berates his parents for leaving the sacrifice to her, and makes him promise never to bring a stepmother into her childrens’ lives. I found myself in exactly Beutner’s reported state of mind at the end of the play. I wanted to know what this outspoken, wilful woman would have done in Hades.

But Beutner’s Alcestis is a completely different breed, from her claustrophobic youth and the loss of her beloved sister to her marriage, controlled by the clash between her father’s wishes and Apollo’s power, and the uncertainty of being married to someone in love with a god and with his male companions. She isn’t recognized as anyone worth paying attention to until she enters the underworld, and that is a mixed blessing as Persephone decides to seduce and enthrall her.

Yet taken together, these two stories of Alcestis are like two bookends. In one, it is the days before her death that give Alcestis voice. Euripides doesn’t care what she says after her return: why should he? She has already said it all. Beutner’s Alcestis, on the other hand, becomes herself only when she dies, exerting her agency after death in the choice to keep silent about what she discovered. Two bookends: one Alcestes speaking before her death, one after. Where Beutner’s book most satisfies is that she has done what she set out to do and shown us what lies between, in the mysterious underworld.