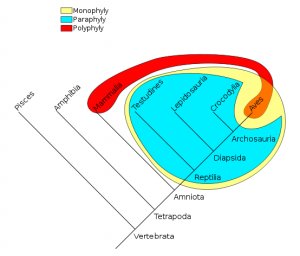

Phylogenetic groups, public domain via Wikipedia. Birds and reptiles are grouped together on shared evolutionary novelties; birds and mammals, on the single significant trait of being warm-blooded.

This was a big issue in my previous life in the world of systematics. The field was in a huge paradigm war between people who classified dead fish based on shared evolutionary novelties (the cladists) and people who classified based on the most significant shared characteristics, the classical evolutionary synthetics of the historical greats. Cladists won this battle, which at the time even participants realized was not one of the great disputes of history.

Only now I begin to believe it was one of the great disputes of history, or at least it should be. Because misclassifying our fellow citizens is becoming a real thorn in my side, and leading to misunderstandings with public significance.

For instance, right now too many of my friends apply evolutionary synthetics to people who don’t support Clinton. Not supporting Clinton is the most significant characteristic for them, so Berniebros like me are in the same group with Ted Cruz. What useful generalizations can be made about this group? None that I know of, but that doesn’t stop the constant stream of posts about how we are all sexist, despite the fact that so many of us Berniebros love Elizabeth Warren.

If we applied cladistic methods to classifying the group of ‘not supporting Hillary,’ we would realize that it is completely divorced from reality (polyphyletic, for jargonistas). Like the bird-mammal grouping in the illustration, it consists of parts of two widely different groups, which cannot be expected to resemble each other in anything except the one characteristic the group is based on. They would be better classified by their evolutionary novelties: Berniebros, Trump fans, Tea Partiers, neoliberalism-haters. None of these groups have much to do with each other, and predictions based on one group will not help you manage the other groups.

This problem afflicts every social issue I can think of. When we classify by the most significant characteristic instead of the novelty that unites a group, we do not see what’s going on. Should a college classify all the students who didn’t enroll in one big group, or look at the students who left after a certain event as a distinct group? Should we lump together all people who are blocking the street during a protest, or distinguish the people who came together in the church van from the people who live on that street? Should I lump all the students who are passing my classes together, or distinguish those who already took it somewhere else from those who are being exposed to it for the first time? Should a pollster ask whether people feel the country’s ‘on the wrong path,’ or break them down into people who feel it’s becoming too socialist and people who feel it’s not socialist enough?

The answer depends on if we want to accomplish something, make useful generalizations and predictions, or just massage our presuppositions about what’s significant.