There’s a place under the world, or perhaps beside it, where you’ll find the old gods. Perhaps you’ll step through a reflected door, or find yourself tumbling into it by accident, or follow a woman who’s been turned into a bird … but once there, you’ll be among the creatures of legend and fairytale and other strays like yourself, who had nothing to hold them in the everyday world…

There’s a place under the world, or perhaps beside it, where you’ll find the old gods. Perhaps you’ll step through a reflected door, or find yourself tumbling into it by accident, or follow a woman who’s been turned into a bird … but once there, you’ll be among the creatures of legend and fairytale and other strays like yourself, who had nothing to hold them in the everyday world…

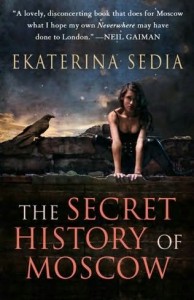

It’s a familiar story, one of the most familiar stories. But in The Secret History of Moscow, the everyday world Ekaterina Sedia’s protagonists escape from is Moscow, during the transition from communism to whatever it’s now called — and the underworld’s denizens are the creatures of Russian mythology, from the household imp who shrieks and throws onions to the cow who created the stars and the twin parasites that suck away a person’s luck. The sheer variety and novelty of the creatures makes her underworld as vivid and fascinating as Russian lacquer.

Yet there’s a layer of soot over this fantasy landscape. Perhaps the protagonists bring it with them from their dreary topside lives, but people in Sedia’s underworld claim over and over that it’s not a happy place, but a refuge for those in extremity. It was this bleak undertone that made me close the book with a dissatisfied feeling. What kind of life did the heroine strive to rescue her sister for? What kind of life would she have herself? Would anybody in this world, above or below, know anything but regret and dissatisfaction? Was abandoning one’s humanity the only escape?

Reading this book left me with more questions than answers. It reminds me of many similar books I’ve read recently, which establish an outsider protagonist who is enough of a misfit, in a miserable enough world, to make his/her choice to enter fairyland plausible — but the aura of misery seeps over and sullies the very fairyland that was presented as an escape.

I don’t have an answer for it. In fact, I fear that the underlying problem is with ourselves. We no longer look at Narnia-like fairylands with an uncritical eye; we see that the feel-good answer they provide is based on oversimplification and the promise of a world where you don’t have to question things that really ought to be questioned. Which is certainly true. But it’s also true that this is what many fantasy readers long for, as potently as romance readers long for the happy-ever-after ending. So what kind of fantasy, fairy-tale reward can be offered us that doesn’t require (or allow) us to check our brains at the door? This is something the fantasy writers may be discovering along with the readers.

For me, as far as I can tell from my own writing, it’s work and discovery. The rewards awaiting my protagonists always seem to be new research topics, new lands to explore. Perhaps that’s what I was missing in Sedia’s underworld. Nobody seemed interested in exploring the place where they had landed, except during one lyrical interlude in Berendy’s forest. I’d love to read a sequel in which a brash, exploration-minded optimist stumbled into the same territory and gave us a different look at it — but perhaps, as the denizens tell us, such a person would never be desperate enough to find the door into this fairyland. Perhaps these creatures will never be seen in the technicolor version I would like. Still, I’m grateful for the introduction to them.