This tutorial will take you through the sequence of events in the inflammatory response.

You can navigate through this tutorial using the buttons at the top of the screen.

The tutorial will ask you questions. Click on your chosen answer to see feedback; click the answer again to make the feedback disappear. When you're finished with one page, click the navigation button for the next page to move ahead.

Have fun! Click on button '1' to see the first page of the tutorial.

Page 1

Inflammation is a response to cell injury, so to understand it you need to think about what your body needs when part of it is injured.

What does this finger need?

Obviously, it needs to stop bleeding.

If there's any dirt in the wound, that will need to be removed. Dead cells will have to be cleared out, as well.

If there's an infection, that must be cleared up - and prevented from spreading around the body.

And the cells will need to grow and divide to fill in the injured area with healthy tissue - which will require food, oxygen, water, and a blood supply to carry the wastes away.

These are a lot of separate things your body has to do, and this situation occurs often, so it isn't surprising that your body has a routine for doing all this stuff as one system. That is the inflammatory system, and that explains why a lot of the same things happen in your tissues whether they were injured by a paper cut, a stubbed toe, or a burst appendix.

Page 2

What will start the inflammatory response? After all, we can't have it just starting at random - it has to start when cells are damaged, and only then.Cells mainly communicate through chemicals, so that's how they start the inflammatory pathway. The chemicals that start inflammation are called inflammatory mediators.

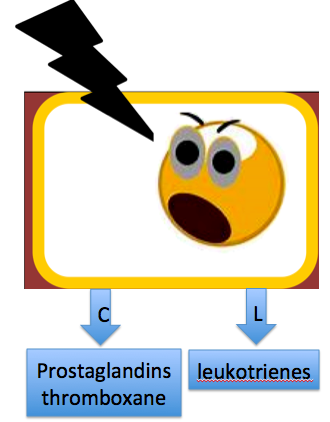

The whole thing begins when a cell is injured and arachidonic acid is released from its damaged membrane.

The arachidonic acid is acted upon by COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, producing compounds called PROSTAGLANDINS (PG) and THROMBOXANE. Another enzyme called lipoxygenase turns Arachidonic acid into LEUKOTRIENES. These are the compounds that start the inflammatory reaction.

graphics from Microsoft clip art

Medication application

COX-2 is the enzyme mainly responsible for prostaglandin formation in inflamed tissue. COX-1 has other effects in the body, including most thromboxane production and protective effects on the gut lining.1 That's why aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), which inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2, reduce inflammation - but also upset the stomach.1-Patrono, C., & Baigent, C. (2014). Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and the Heart. Circulation, 129(8), 907–916.

Page 3

What if the injured cell was too badly hurt to make prostaglandins? There's a special group of white blood cells called Mast cells living scattered throughout the body, sort of like first responders. Mast cells are filled with granules containing inflammatory mediators, which they release when nearby tissues are damaged.One of the major inflammatory mediators in those granules is histamine.1

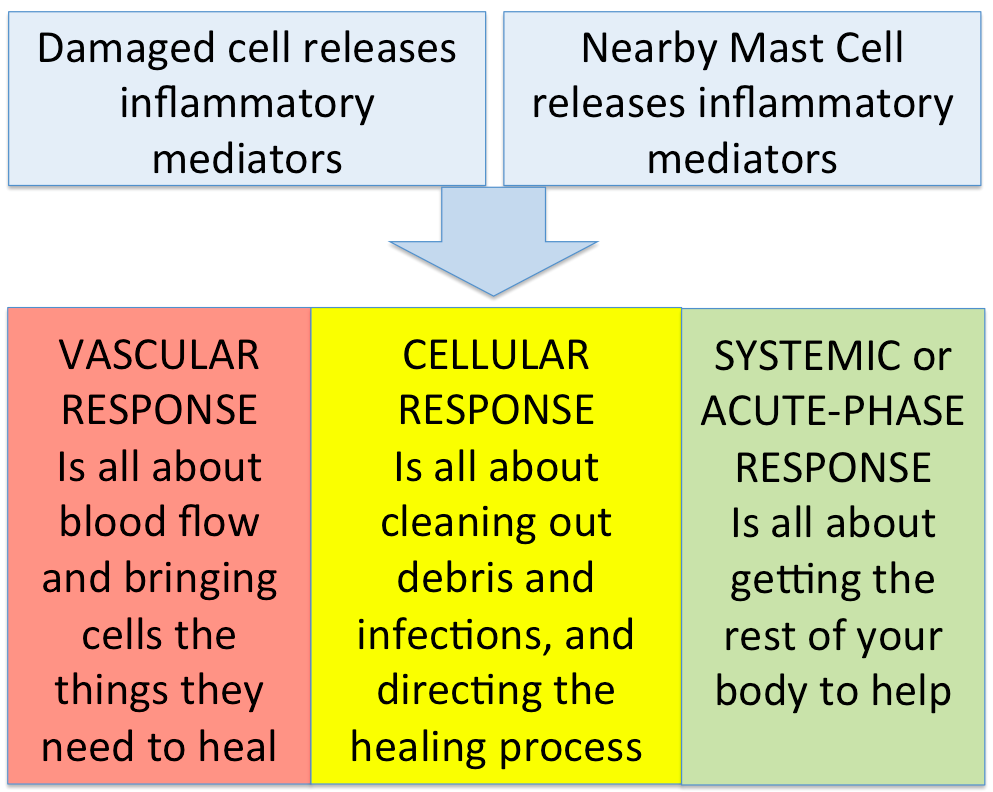

Now the injured area has been flooded with inflammatory mediators: PROSTAGLANDINS, LEUKOTRIENES, THROMBOXANE, HISTAMINE. These will start a cascade of responses to make sure the tissues get what they need to heal. The inflammatory responses can be divided into three parts:

1-Mandal, A. (2010, February 18). What Does Histamine Do? Retrieved May 1, 2016, from Medical News.

Page 4

The Vascular Response

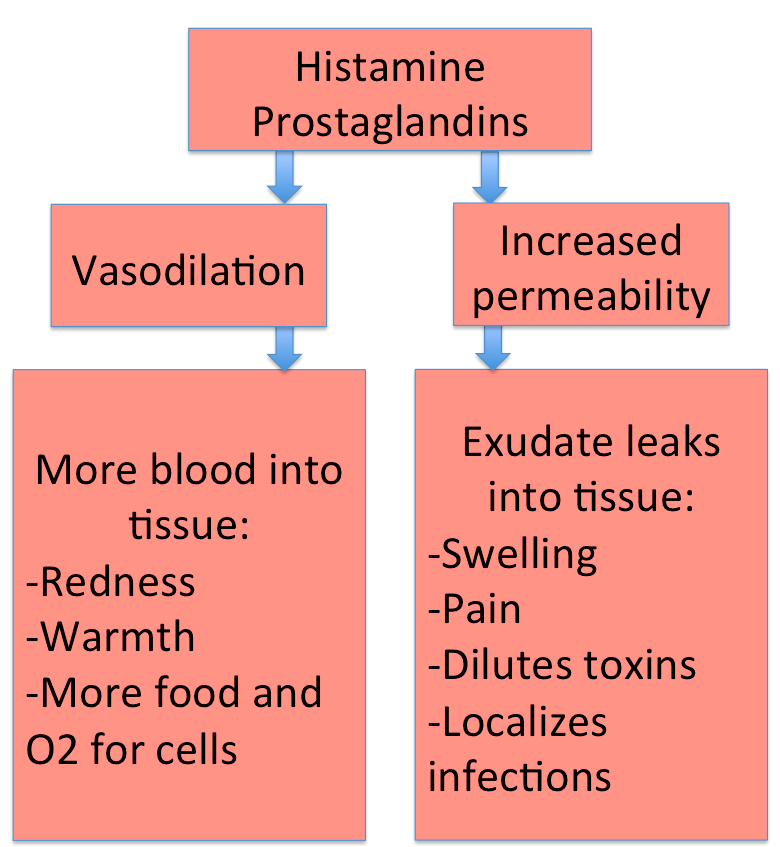

Vascular means vessels, so this is all about blood vessels. When inflammatory mediators reach the blood vessels, they have several effects.For a split second the vessels constrict, but then they dilate, opening wide to let more blood flow into the injured area. This vasodilation causes the redness and warmth that are two of the cardinal signs of inflammation. More importantly, the blood is now bringing plenty of food and oxygen to the injured cells.

With all that blood flowing into the tissue, though, will bacteria from the wound hitch a ride in it and leave the area? That's a real danger. It's less likely, though, because the blood vessels' second response is to become more permeable, or leaky. A lot of the fluid coming into the tissue in the blood vessels leaks out of the vessels and stays in the tissue, instead of flowing on through. This can help healing in several ways:

1. The fluid will dilute any poisons that are in the wound

2. The fluid can help wash poisons, dirt, and pathogens off the surface of the wound

3. Since the fluid isn't leaving the area, it's hard for infectious organisms to leave with it

This fluid is called exudate, and it causes the swelling that is another cardinal sign of inflammation. The swelling presses on pain nerves, causing the pain that is another cardinal sign.

The exudate dripping out of your nose is serous or watery exudate. There are other kinds!

Fibrous/Fibrinous exudate has fibers in it like the fibers that make clots. It forms in hollow organs and spaces, covering bacteria and trapping them.

Purulent exudate or pus has white blood cells in it - a sign that the area is infected.

Sanguinous/serosanguineous exudate has red blood cells in it.

Now you know about the vascular stage of inflammation, make a prediction: will a large-scale inflammatory process raise or lower your blood pressure?

HOLD ON THERE! REMIND ME OF THE BLOOD PRESSURE EQUATION!

Raise it, because the cells need more blood

Page 5

The Cellular Response

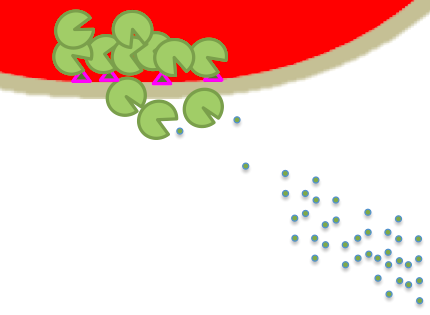

There's one more important thing that the blood vessels do when you have an inflammation: they begin to make adhesive proteins.

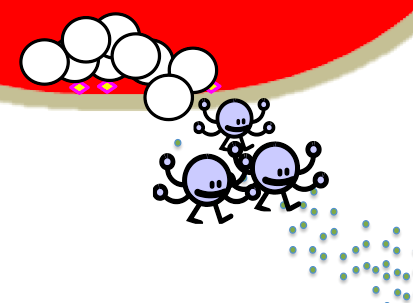

The cells on the blood vessel lining start to create special proteins that platelets and white blood cells can stick to. When platelets adhere to the vessel in the injured area, they will form a clot to stop the bleeding. When white blood cells come floating by in the blood, they too will adhere to the vessel lining. Pretty soon a crowd of white blood cells will have stopped in the area, the way people stop to stare at any accident. Except that being cells, with no eyes, they are more like smelling at the accident - smelling all the inflammatory mediators that were released by the injured cells and the mast cells.

Once they reach that area, the neutrophils get to work clearing it up. They eat bacteria and secrete digestive enzymes to break down any damaged cells, getting the rubble out of the way so your tissue can rebuild itself.

This makes neutrophils very powerful for dealing with infections - but it can also make them a big problem, if they don't know when to stop. In many chronic inflammations, the neutrophils just won't quit damaging the tissue, even when it ought to be healing!

Page 6

The Cellular Response continues...

Now the neutrophils are in the damaged tissue, cleaning up all the debris. But neutrophils don't build; they tear stuff down.

Lucky for our damaged tissue, the blood vessels made adhesive proteins for more white blood cells than just neutrophils. Another crowd of interested cells has accumulated in the vessel - the monocytes. And they are also attracted to the chemicals released by the mast cells.

When the monocytes crawl out into the injured tissues, they undergo a startling transformation! They grow tentacles and develop the ability to create huge amounts of inflammatory mediators and growth factors. Now they have a new name - macrophages, or 'big eaters', and they will play important roles in directing the healing process and in protecting the body from infections in this damaged area.

Right now, though, they and the neutrophils are all busy eating bacteria and releasing inflammatory mediators. Among those compounds are cytokines. If there is a bad enough infection, and enough neutrophils and macrophages releasing cytokines, these compounds will get out into your blood and be carried throughout the body.

Page 7

The Systemic or Acute-phase response

When the cytokines get into your bloodstream, the rest of your body discovers what's been going on in your injured tissue.

image by LadyofHats,from Wikimedia commons. Used under a creative commons license.

-Cytokines in your brain make you feel sick and sleepy - malaise.

-They re-set your internal thermostat, making your brain think you need to be warmer. Now you start to shiver, or bundle up in warm clothes, and your temperature does rise. You have a fever.

-Cytokines stimulate your liver and other tissues to produce C-reactive protein, an antibacterial compound that also stimulates more inflammation.

-The cytokines hit your bones and make the bone marrow start producing more white blood cells. Your WBC count increases.

-All through your body, cytokines irritate pain nerves, causing muscle aches (myalgia) and joint aches (arthralgia).

All in all, the cytokines make you miserable. Stop running around! Go to bed and let the macrophages and the damaged tissue use all the energy they need to heal you!

Page 8

Inflammation summary

Think you have the basics down? See if you can choose the right terms in this summary.

When your tissues are damaged, lactic / arachidonic acid is released from their membranes. It's converted into inflammatory mediators / cytokines. One group of these is called prostaglandins / NSAIDS.

As well as the damaged cells, nerve / mast cells in the tissue release more compounds, including lactic acid / histamine.

These compounds affect blood vessels, causing them to vasodilate / shrink. This decreases / increases blood supply to the injured tissue and causes two cardinal signs of inflammation: pain and swelling / redness and warmth.

The blood vessels then develop decreased / increased permeability. Exudate / CO2 is formed, causing two more of the cardinal signs of inflammation: pain and swelling / redness and warmth. This response is called the Cellular / Vascular Response.

The blood vessels also created adhesive proteins on their linings, to stop passing white blood cells. The first cells to stop and crawl into the injured tissue are the neutrophils / macrophages, whose main job is to heal the tissue / remove debris. Next come the mast cells / monocytes, which mature into neutrophils / macrophages after they enter the tissue. Once there, they help eat invading pathogens and release growth factors to direct healing. This response is called the Cellular / Systemic or Acute-Phase Response.

All of these white blood cells secrete cytokines / histamine. When these chemicals get into your blood, they affect your brain and cause cold sweats and anxiety / malaise and fever. The same chemicals make your bone marrow create more white blood cells / create more red blood cells. This response is called the Cellular / Systemic or Acute-Phase Response. It makes you feel miserable and go to bed.

If you're lucky, and stay out of the way of your inflammatory system, the injured tissue will heal itself! If you have an infection, though, your inflammatory system may have to call in the adaptive immune system. That's another tutorial, though.

Sources used in creating this tutorial include:

Porth, C., 2015. Essentials of Pathophysiology. 4th Edition. Lippincott, Philadelphia, Pa.