Beetle Specimens in a Lab, by Steve Winter. You can buy a poster from http://fineartamerica.com/art/all/biodiversity/posters. You know you want one!

I stayed so long in graduate school that they put me in the museum. Was this supposed to motivate me to finish? It didn’t; I liked being up there in the dry specimens’ collection, able to drool over the cases of stuffed hummingbirds whenever I wanted. It only confirmed my belief that a museum is a great place to work.

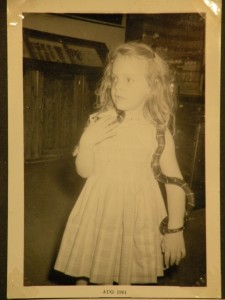

I had actually hung around museums all my life. Most of the places my father worked had small but serviceable museums, and I have a photo of myself at 5 playing with a live king snake in one of them.

note the cases of beetles in the background

In undergrad, my biology club took on the jobs of labeling the collection and creating weekly informational displays, jobs which involved maintaining live squirrel monkeys and an ill-tempered rattlesnake. In grad school I hung out in full-fledged research museums, with people who retrieved dead manatees and skeletonized them, skinned bats and flamingos, and on one memorable occasion took apart a dead grizzly bear next door to my office, playing loud country music throughout the process. People used to mistake my office for the museum, and once a man strode in and flung a dead Golden Eagle onto my desk.

In museums, collection preparation, maintenance, classification and documentation are the order of the day. The Royal Academy’s museum is no different. It is run by a small staff team, who do not always keep up with their work. Here’s Linus Ukadnian’s first impression of the prep room, in Kindling:

Every surface was cluttered three deep with open books, unwashed dissecting instruments, a blowtorch and glass tubing in the middle of being made into something, skeletal forelimbs still bound together by desiccated cartilage, tufts of feathers, birdlike feet curled up into dry claws, unraveling reels of string and wire, wadded netting with seaweed in it, petri dishes whose contents had dried or gone to mold, and random scraps of paper. Toward the back of the room, the mess was larger and more disgusting. The rib cage of a hippogriff was there, only partly denuded of flesh, and a dragon’s head lay next to it, its dried-up eyes glaring back at Linus from deep sockets. A great glass tub held something half-hidden in scummy liquid, pressing scales against the glass in one place and a bloated, human-looking hand in another.

Of course Linus tries to shape this operation up, but runs into more difficulties down on the live specimens’ floor, which unfortunately is not restricted to live specimens:

He stood at one side of a cavernous room, the long wall in front of him lined with hay-strewn stalls over whose swinging doors came sunlight, breezes hot, cool or damp, birdsong and rustling leaves. A cat-flap in one of the stalls stirred and a long nose, pink and quivering, poked through. The eye following it gave Linus a panicked stare, the nose pulled back and the flap clacked shut.

Linus stepped forward, charmed, until his foot struck something – a coffin!

All this reminiscence is prompted by Bug Girl’s tweet about this article from NaturePlus, about the international network of beetle experts. Beetles in museums … every museum has them: if not in the collection, then in the prep room, being used to skeletonize small specimens. But only the Selanto Museum has an expert making them.

In the old days, before the Mystic Guild of Alchemists was formed, alchemists used to make whatever kinds of animals they could dream up. Hence the fantastic variety found in out-of-the-way places, creatures that look as if somebody was trying to ring every possible change on his new idea. Nowadays, however, this sort of exuberance is discouraged by the Guild. There are too many people around, and not enough space for new animals, so animal alchemy has been reduced to a few small research programs. At the University of Selanto, they focus on beetles. A single alchemist there spends his days dreaming up new beetles, thus keeping the international beetle community in business.

You might ask, why beetles? For an answer, you will have to visit Selanto and search out his office in the basement. Or you could visit your local museum and look into just one case of beetle specimens, and then you will understand for yourself.