It’s been a while since I devoured a book the way I devoured this one, which arrived at my door 4 pm yesterday. And it’s been a while since devouring a book left me with such a feeling of having a lot to digest.

It’s been a while since I devoured a book the way I devoured this one, which arrived at my door 4 pm yesterday. And it’s been a while since devouring a book left me with such a feeling of having a lot to digest.

As soon as I unwrapped the book, I sat down on my front porch and started reading it; but I only got about 15 minutes in when some friends arrived for a dinner date. Over dinner we talked about a lot of things, including online bullying and controversy. “I hardly ever sign online petitions any more,” my friend said, “because everything turns out to be a lot more complicated than it was presented to be. I could spend a year trying to figure out the actual facts of the case.” And then, we agreed, the controversies too often turned into exercises in taking sides. But did being cautious lead to not intervening when you really ought?

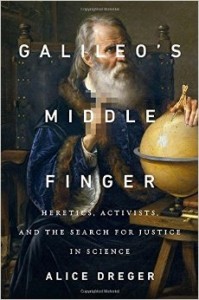

Galileo’s Middle Finger is basically about that. It’s a call for evidence-based activism, for the need to understand what is actually happening in order to change it. It doesn’t offer any useful tips for the person faced with one of those online petitions, however – and that may be the point.

In the book’s first section, Dr. Dreger outlines the kind of historical research she did to understand the concept of intersex and how it led her into activism against gender reassignment surgery. What surprised me most, I have to admit, is her admission that at the beginning of her studies she didn’t even know that hermaphroditism occurred in humans. What impressed me most was that she had the skills to turn her research findings into successful activism, something which has always struck me as miraculous.

Having this body of information and experience under her belt, she then turned to research on conflicts between researchers and activists. As someone who had been more familiar with the ‘republican war on science’ literature, I was surprised to find how much conflict had occurred between the progressive community and scientists and how adeptly right-wing figures had latched on to whatever parts of that controversy they could use.

Dr. Dreger gives detailed, gripping examples of the kind of fact-checking necessary to make sense of such controversies – reading the references to see what’s actually in them, delving into the archives of professional societies, soliciting old e-mails from ex-members of review boards. But the shadow side is that her enemies, those condemning the scientists she champions, are doing the same things. They, too, are traveling to interview research subjects. They, too, are soliciting information from in-country sources; they, too, find their opponents’ arguments to be nonsense and their opponents’ evidence to be a tissue of lies.

What’s the difference between them, then, for the person not able to spend years looking up every cited article? Well, in the middle of the book social justice rhetoric and overt hostility seem to be pretty clear hallmarks. Folks more motivated by ideology than by devotion to the truth are the ones to distrust. But then, in the last section of the book, Dr. Dreger pulls this rug out from under our feet.

In the last section, Dr. Dreger becomes involved in the case of prenatal dexamethasone treatment to prevent virilization in female infants with CAH – and the book circles back, like a spiral staircase, to where it began but (perhaps) on a higher, more sophisticated level. Because now she is the person attacking a researcher, getting people to sign letters of concern based on her word rather than their own research, using many of the methods she’s been poking holes in.

You’d think that if anybody was qualified to answer the question How do you stop a scientific researcher?, it would’ve been me at that moment. The problem was that my work had only uncovered all the wrong ways to do it. What the hell was the right way? (p. 191)

One of the touchstones Dr. Dreger clings to to distinguish herself from activists who have lost perspective is that she will follow the evidence, in this case the evidence of an FDA investigation; if that investigation finds no wrongdoing, she will accept that she’s been wrong. But when that happens, it doesn’t turn out to be enough to overturn her judgment. Instead, like the other activists who refuse to be convinced earlier in her book, she returns to research, digging deeper – finding conflicts of interest, parsing details of grant proposals, writing articles until critiques of the science in question dominate any google search for it. And while of course I’m on her side – because she wrote the book, and I’m in her POV – I can’t help wondering if this looks one bit better than her previous examples, or one bit more evidence-based, to the scientist involved. And all the advice she gives us throughout the book on how to continue your work in the face of people trying to stop you could be as easily directed to, or coming from, that scientist.

So what does the person trying to make sense of such events do? Dr. Dreger’s advice is clear. Insist on evidence. Do the research. There’s no shortcut to knowledge. I like it! But then I would like anything which tells me I need not act without having written the equivalent of a thesis on a topic. Is this a recipe for quietism, and for ceding power to the folks who can finance multi-year studies or who are obsessed enough to conduct them for free? I remember Bruno Latour’s diagrams of how scientific discourse buttresses itself against the outside reader, and I am not at ease.

The most important thing I take away from this book is a renewed feeling for the duty and obligation one takes on when agreeing to review – especially to review controversial situations. In one of the stories Dr. Dreger recounts, a professional organization decides that it has to take a ‘piece of sleaze’ attacking one of its members seriously to avoid being tarred itself by the accusations. In another, the person running an investigation is in job negotiations with the journal publishing polemics against the investigation. Undisclosed conflicts of interest stud parts of the story like raisins in fruitcake. This sort of thing cannot be endured, cannot be participated in, by people who care about science or research. What does it cost to recuse yourself from something, for heavens’ sake?

I also see a lesson for the scientific community as a whole. Too many of the scientists in this book went through controversies without any social support to speak of – and whether they are right or wrong, what is gained by isolating people involved in the knock-down drag-out of competing truth claims? Being wrong is part of scientific practice, and we cannot keep science healthy when folks divide themselves into camps of partisans and admitting errors becomes a career-ending surrender. As scientists, we should be more concerned with the health of our field than with positioning ourselves on the ‘right’ side of specific controversies.

Galileo’s Middle Finger isn’t an example of unimpeachable, obvious scientific rectitude. It’s too messy, too ambiguous a story for that. But it’s a rousing reminder from the front lines that there are ideals we have to aim for even if we know we will fall short, and that it’s the duty of the academy and the profession to support its members in the attempt.

What if we came together in the ivory towers, barricaded the doors, and looked at the skies? (p.133)